If you are someone who speaks or aspires to speak at professional and industry conferences or similar events, then it is almost certain you will need to record a virtual presentation at some point.

To do that you could, of course, just fire up Zoom and record yourself narrating a slide deck, possibly with your tiny self-visible in a video box off to the side.

You could. (Yawn.)

Or you could put in a little effort and create something event planners and attendees are much more likely to find engaging – and that will result in your attendees actually learning something. (What we’re all about here at Learning Revolution.)

In this post, I’ll go through the steps I follow. I can’t claim to have mastered them, but I do know they are rooted in learning science, and they result in presentations that are much more engaging and impactful than what you usually get at virtual conferences and other virtual events.

We’ll get to the details momentarily, but first let’s consider why it matters

Virtual Events Are Here to Stay

Given that it looks like everything may return to “normal” soon, you may be asking “Why should I care about how to record a virtual event presentation?”

Clearly, we saw a huge surge in traditional events moving online with the emergence of COVID-19 and it’s tempting to think that as the pandemic recedes, all those events will simply go back to their usual face-to-face settings. Some will, of course, but a lot won’t.

Why? Having been forced to go virtual, many organizations have now realized that it has a lot of benefits. For example, with a virtual event, the average organization:

- Saves a lot of money on event costs

- Takes on a lot less risk (e.g., no food and beverage or hotel block commitments)

- Has the potential to reach many more people than with its face-to-face events

While many – maybe most – organizations will return to face-to-face with their flagship events, the idea of making these “hybrid” – i.e., with people participating both in-person and online – is currently all the rage in the events industry. And, that trend aside, many organizations will make the switch to virtual permanent for their smaller or second tier events and will likely add new virtual event offerings to their portfolio.

As part of this shift, many organizations have realized that there are significant benefits to getting most of the presentations for a virtual (or hybrid) event recorded in advance. Getting not only slides but entire presentations in advance offers a lot of peace of mind to stressed out event planners. Presentations can then be replayed at a scheduled time, often in combination with live chat. For speakers, this offers the benefit of actually engaging with attendees in the chat – often very hard to do when delivering content in real time.

Overall, the greater ease, convenience, and cost savings represented by virtual events – along with the pandemic having pushed them into the mainstream – means we are likely to see as many or more of them in the post-COVID world. So, there is a ton of virtual opportunity for speakers.

But that brings us back to virtual presentations.

Expectations Are on the Rise

As organizations have gotten used to hosting virtual events and attendees have gotten used to participating online, expectations have gone up. A lot. The average talking-over-PowerPoint presentation that has been the mainstay of Webinars for years just doesn’t cut anymore in most cases.

It’s not that these types of presentations can’t be good and useful. It’s just that most of them aren’t, and never have been. And now that attendees are being subjected to an even higher volume of them than usual, patience for them is dropping fast.

In some cases, event planners and attendees are vocal in complaining about them. I see this a fair amount on association discussion boards that I frequent. More commonly, though, attendees simply tune out or (because their expectations have rarely been met in the past) simply don’t show up.

Now, if you are a speaker, regardless of whether you get paid for it, you probably have goals like building a brand for yourself and your business and actually having a positive impact on the lives of the people you address.

So, a presentation that sucks just isn’t good for anyone.

On to the “how-to.”

1. Plan It, Script It

When you present in a live face-to-face setting, you have a good bit of wiggle room. It’s pretty easy to speed up, slow down, or even drop entire sections of your content on the fly. With slides as a backdrop (or crutch) and a rough outline or notes, many speakers make it through these types of presentations with relatively little planning or practice.

This is a much harder approach to pull off with a recorded virtual presentation.

In the first place, there is almost always going to be some sort of time constraint for your talk. If the event planner tells you “25 minutes” for example, you may be able to come in a few minutes short or long, but any more than that and you may really screw up the timing for the event.

So, ideally, you need to have a solid idea of how long your content will run before you press record.

Second, because you will not be able to answer questions as you speak or adjust your content on the fly, it pays to really think through the most essential points you want to make and figure out how to make them in the most logical, concise, and compelling way. (Of course, good speakers should also do this with their live presentations, but let’s face, many don’t.)

Fortunately, there is a sure-fire way to address the issues I’ve just raised: write out your entire presentation.

I can feel groans rumbling through my keyboard even as I write this, but really, there is no better way to make sure you have you content structured effectively and that you can deliver it in the time allotted. We know very well, after all, the number of words that correspond to a minute of speech. Using an online calculator like this one, you can easily determine how many words you need to write.

Now, it’s possible that with a general idea of the number of words you are aiming for you can manage to work off of just an outline and notes. Good for you if you can, but I’ve never found that to work well. I strongly prefer to script the whole presentation and either memorize it or read it (with the help of a simple teleprompter like this one). Either way with enough practice runs so that I am able to do it naturally.

As I write, I have four key aims in mind, which leads to my next point …

2. Nail the Opening

First, I want to make sure the introduction pulls attendees in as much as possible. Again, this is a good practice for any presentation, but I think it is particularly important for recorded virtual presentations. Attendees can check out very quickly – whether figuratively or literally – if you aren’t able to engage them in a meaningful way right at the start.

So, “Hi, I’m Jeff. So nice to be here” isn’t a great start.

My stand-by for introductions is to share a story or anecdote with just me on screen – usually no slides, at least for the first minute or so. I think of this story as a sort of “landing page” or sales page for the entire presentation. Its purpose is to move attendees to “buy in” to watching and participating in the rest of the presentation. With that perspective in mind, it can be useful to borrow the classic AIDA approach used by marketers in deciding on and structuring your story:

A: Attention – Offer content at the very beginning that will grab attention. This may be a provocative statement, question, or quote; it may be an image; it may be the setting you choose to film yourself in or just something about how you present yourself on screen. Really, the possibilities are endless.

I: Interest – Grabbing attention purely for the sake of attention is pointless (and can be annoying). How can you build on the attention you receive to foster deeper interest? Usually, this will mean pivoting quickly to establish the relevance of your opening attention grabber to your audience. It means beginning to establish the “why” of your presentation for the audience you are addressing

D: Desire – Interest is a necessary step beyond attention, but for attendees to really engage with you and your material, they have to see the potential for value and applicability in their own lives. This is the classic “WIIFM,” or “What’s In It For Me” aspect of adult learning. While you don’t have to explicitly address the WIIFM aspect of your presentation in your opening, there should be a strong enough sense of it that attendees want to – better yet, feel compelled to – stick around to realize the value that your presentation promises.

A: Action – A good sales page includes a clear “call to action,” and so should the opening to your presentation. Each of the three steps above lead to the action you want from your attendees: a commitment to watch and participate in the remainder of your presentation. You may ask for this commitment more or less overtly, depending on the nature of your opening, but it should be clear as you transition to the next part of your content that you want and expect your attendees to come along for the ride. This may literally include asking them to acknowledge – to themselves or in the chat area, if there is one – that they are committed to participating.

While addressing each of the components of AIDA may seem challenging, there are few things that make a bigger difference in how a presentation is received than the opening. It sets the tone; it sets expectations; it establishes a sort of agreement with your attendees. A strong opening builds momentum that can carry attendees through even weaker parts (there are always some!) in the remainder of your presentation.

A story, of course, is just one approach. Another one might be to present some sort of challenge or problem that is relevant to the topic and the audience. Present it and then build in some time in which you are silent and allow attendees to work on the problem before you present a solution. Or, present a thought-provoking question, a quote from a well-known thinker or practitioner, or a compelling image. Any of these can be a door into gaining attention, exciting interest, developing desire, and asking for action.

One final point: While I’ve relied on a marketing inspired approach here, I’ll note that all of this jibes with what research in cognitive and behavioral science has taught us. Establishing and sustaining attention is critical to learning as is taking action. Helping these things happen is the essence of good teaching, and that’s exactly what a strong opening step you up for.

Again, all of this is even truer with presentations that are both virtual and recorded. So, it is well worth devoting a significant amount of your thinking, planning, and writing for any virtual event presentation to nailing the opening.

Here’s an example of an intro segment I did for a session on learner engagement for the California Society of Association Executives (CalSAE). I’ll leave it to you analyze how well I do – or don’t – practice what I preach in this one.

3. Cut and Chunk

As important as the beginning of your presentation is, the real substance of it is in the content that follows. That means you need to maintain attendees’ attention, focus it on your most important points, and do what you can to support longer-term retention and application of your material.

When you think about it, that’s a tall order. The 30 to 60 minutes an average presentation lasts isn’t much time for achieving any real impact, and yet, it is also a very long period of time to keep the average person’s attention – especially in a world of cell phones, social media, and other distractions.

So, how you put your content together is critical. Just riffing to your slides will rarely cut it these days – especially if you want your attendees to actually learn something and retain what they learn.

First, get crystal clear about your objectives

Your starting point for achieving that is to get ultra-clear in your own mind about the objectives of your presentation. The objectives represent the strategy for the course and should drive decisions about content—what stays, what goes; what approaches are most useful, etc. In short, your objectives determine what it is most important for your learner to pay attention to in the course.

To clarify your objectives, ask, “How should attendees behave (differently) as a result of participating in my presentation?” Even if you see your presentation as primarily informational, be clear about what the learner should be able to do with the information. How will she apply it in the real world?

Keep in mind that only so much information can be absorbed and only so much change can be prompted by a single presentation. Most presentations suffer from a lack of clarity about objectives, too many objectives, or both. Exactly what will amount to too many objectives will depend on a range of variables – from the complexity of the topic to the background of the learners – but as general rule, it’s best to aim for achieving no more than two, possibly three objectives in a one-hour session.

Then, on to cutting and chunking

Once you have your objectives clear, focused, and reduced to a realistic number, you can move on to cutting and chunking.

As a presenter, you no doubt hope that your attendees will remember everything you share with them, but you also no doubt recognize that human beings have limited capacity for memory. More technically, we can only hold so much information in our working memory, the type of memory involved with storing, focusing attention on, and manipulating information for a relatively short period of time, time measured in seconds. Learning is a process of bringing information into working memory and then moving it into long-term memory—which, as far as we know, does not have any limitations.

The amount of working memory resources used for a task or in a situation is referred to as cognitive load, and, as a presenter, you want to do what you can to keep cognitive load at as manageable a level as possible for your attendees. This effort often starts with resisting the temptation to share everything you know about a subject and being disciplined about cutting content that is not truly relevant or germane for achieving your targeted learning outcomes.

To cut, go back to objectives: What is it truly necessary for the learner to know to achieve the desired outcomes? What is extraneous or perhaps “nice to know”?

Literally, list these out. It can help to know that “nice to know” information doesn’t have to totally ignored. You can still make this available in a number of ways—through resource pages, downloadables, and other types of “bonus” content. But get it out of the main flow of the content that is truly targeted to achieving the objectives.

Next, chunking longer content into shorter segments and allowing for brief pauses before continuing on from one segment to the next will also help to keep cognitive load at manageable level. Shorter segments—typically meaning no more than 10 minutes—are more in line with what our limited working memory can process and pauses allow time for that processing to happen.

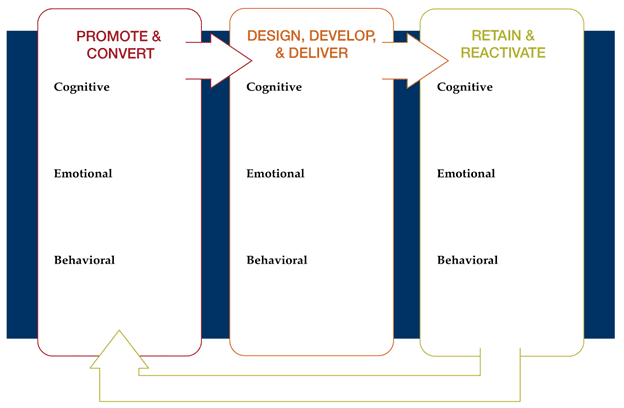

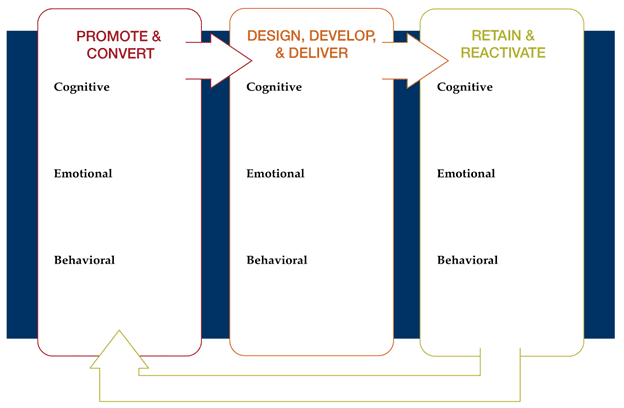

At the highest level, your chunks of content should serve to focus attention on related concepts and information. These would typically be the larger sections of your presentation. In the presentation on learner engagement, I referenced in the video clip earlier, for example,

I chunked the content down into the following top-level segments:

- Defining Learner Engagement

- Requirements for Engagement

- Signals and Support of Engagement

- Accountability for Engagement

Within those major segments, I further chunked the content down into topics that I felt were most essential to those larger concepts. For example, in “Signals and Support of Engagement,” I addressed:

- Promote and Convert

- Design, Develop, & Deliver

- Retain & Reactivate

Finally, I chunked the content down further to each individual slide or snippet of video, being careful to try focus on one essential point within each and to try to ensure that I stayed within the limits of working memory in each.

As you might guess, while there is science behind all that effort, there is also more than a bit of art and guesswork to it. I won’t claim to have gotten exactly right – in fact, in retrospect, I’m sure I didn’t. Few presenters do, but practice with chunking over time can dramatically improve your capabilities.

4. Mix media wisely

As you are cutting, chunking, and sequencing your content you, of course, have options regarding the types of media you can use—text, images, audio, and videos, just to name some of the most common examples. Varying the types of media, you use is almost always a good practice. It can help keep a presentation interesting, maintain attention, and ultimately, help your attendees learn and remember what you present.

But again, there are research-based rules that apply to doing it right. You need to be careful to use media in a way that does not increase—and ideally decreases—cognitive load.

In the context of a recorded virtual presentation, the three types of media you are most likely to use are text, audio, and images, so I’m just going to focus on those in providing some guidance. (I know – the whole presentation is a video, but that make video as ort of “meta” medium in this case, rather than something you use as an element of instruction.)

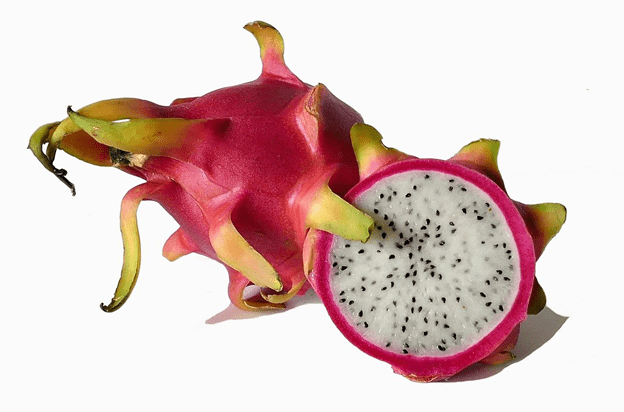

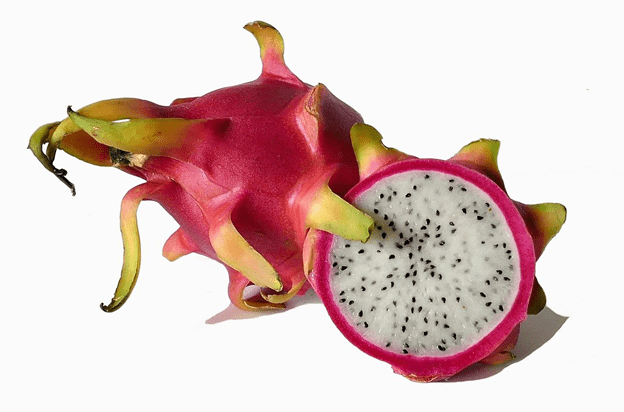

First, research indicates that including images to illustrate key points in your presentation can be an effective way to support learning. And sometimes, it’s the best way. If, for example, someone doesn’t know what a dragon fruit looks like and the goal is to for them to be able to buy one at the market, would it be more efficient to describe the fruit’s leathery slightly leafy pink exterior and its white flesh pitted with black seeds or show a picture?

The picture is more efficient in this case. And you should also consider when using an illustration, a photo, or a graph rather than a verbal description might reduce extraneous cognitive load when making a point.

But using multimedia effectively isn’t as simple as sprinkling a few photos or graphics throughout your slides – and you definitely don’t want to clutter up your presentation with too much media. There are research-based rules that should be followed. Based primarily on the work of Richard Mayer and Ruth Clark, here are four that are particularly important and useful for the average online presentation:

First, use only graphics images, text, and narration that clearly support learning goals. Images that are merely decorative or text that is tangential or supplemental, for example, will only increase cognitive load and make it harder for learners to absorb your key points.

Second, as you are narrating your presentation, avoid using both graphics and text at the same time. While there are exceptions, it generally increases the learner’s cognitive load to have to process both text and audio while also viewing a graphic.

Third, where appropriate, make use of arrows, highlighting, and other signals to draw attention to important information. This practice helps to focus the learner’s attention while also reducing the need for extraneous text.

Fourth, present in a conversational way. It can be easy, especially if you are presenting on a complex topic, to slip into jargon or academic, formal-sounding language. But research suggests that a more relaxed, informal approach can positively impact learning.

There are other rules – and many nuances – for using multimedia in the most effective to support learning. To the extent you want to go deeper into those, I’ve included a few supplemental resources at the end of this article. Just implementing the above suggestions, though, will go a long way toward ensuring you are making the most of the media you use in your presentations.

5. Space and repeat

If your goal is to help you attendees actually learn something – as opposed to purely entertaining or motivating them – then this point, in combination with the next one, is critical: you need to revisit key concepts and give attendees the chance to engage with them throughout your presentations.

You probably know from your own experience that being exposed to information only once rarely results in our remembering it. And a wealth of research supports the idea that repetition is essential for learning—but not just any repetition. The repetition must have two key qualities.

First, it needs to occur over time to be most effective. That is, there needs to be some space between the time when an attendee first engages with the material to be learned and each subsequent time. So, plan to revisit your most essential ideas and concepts at different points in time throughout your presentation. As I’ll discuss soon, it’s also a good idea to provide attendees with ways that they can revisit key ideas and concepts on their own at multiple times following your presentation.

Second, repetition needs to involve some effort if you really want the repeated material stick. The attendee needs to re-engage with material cognitively and—in cases where the learning involves a skill or other observable behavior—physically.

I’ll come back to the importance of effort momentarily, but, for now, it’s essential to understand that repetition is a way to re-focus attention to the most salient material, the material that most supports the objectives of your presentation. For that reason, it’s critical to plan out the repetition and review of key concepts in different ways throughout the presentation.

Along these lines, it’s worth noting that one of the desirable outcomes of the cutting process I covered earlier is to ensure you preserve sufficient time for revisiting material—rather than simply introducing more and more new material. Winding back even further, that same thinking applies to objectives: given the need to repeat key material throughout your virtual presentation, there are really only so many objectives you can address.

6. Provide for Participation

Now, let’s return to that idea of repetition needing to be combined with effort on the part of the attendee. Even in on-demand, recorded presentations, participation from attendees is possible and desirable—but clear opportunities have to be called out and supported.

So, first …

Prompt and pause

As obvious as it may seem, an often-overlooked aspect of participation is that you usually must ask for it and then – here’s the kicker – actually build in sufficient time for it. That means including silence during live presentations (including replays with chat) or – more common in completely on-demand presentations – having attendees hit the pause button to allow time for whatever it is you ask them to do.

Here’s a brief example of me allowing for some silence in a virtual presentation. Note, too, that I use a tactic for commenting on chat even though this is a recorded presentation, and I can’t actually know in advance what will be said in the live chat that occurs during the presentation replay.

Not rocket science, obviously – just one of those things you have to plan for and execute. (Which goes back to the points above about scripting, objectives, etc.)

Yes, doing something like this can feel a bit awkward, but it can really help tremendously with learning and memory. A fundamental problem with most presentations is that the learning evaporates once the learner exits the physical room or online session. To combat forgetting, we have to encourage and guide attendees to “practice” with the material and prompting and pausing creates the opportunity to do that.

I’ll note, too, that prompting and pausing are a way of focusing attention—signaling to attendees what is important and giving them an opportunity to engage and re-engage with that important material.

Of course, once you have focused or re-focused attention in this way, you have to provide the actual participation opportunity – which leads to my next point.

Mix it up

There are many ways to enable participation in a virtual participation – and most of them are not especially complicated. You don’t need fancy animations or elaborate games. Simple methods like reflection questions, contributions to chat, quizzes, challenge problems, or even assignments to be completed later can be quite effective.

Using a variety of methods throughout your presentation can help maintain learner interest. Just as importantly, if you give learners the opportunity to engage with the material in a variety of ways, you’ll be supporting different aspects of learning.

A simple “pop quiz” (i.e., pose a question and pause momentarily to let attendees think about the answer) might help to bolster memory for a key concept; a reflection question might provide a means of “elaboration”—challenging the attendee to think through how the concept applies to her own situation—to something she commonly does back at work, for example. A suggested assignment could then challenge her to apply one or more key concepts when she is actually back in her work context.

To go back to the earlier point about spacing and repeating, it’s highly effective to provide for repeated, but varied types of participation throughout your presentation. You might, for example, pose a problem or challenge as a way of introducing a key concept, and then return to the same concept later, offer a solution, and present a reflection question.

One key in mixing your methods in the most meaningful way is get your attendees to make an effort—to retrieve, to elaborate, to rehearse, to apply, to make their own connections between the material you share and their own contexts. A wealth of research suggests that this kind of effort is essential for making learning stick.

So, as you deliver the presentation, overtly tie your material back to the outcomes and positive change that attendees are seeking. But even more importantly, help attendees – through participation – make such connections for themselves. They’re better able than you are to make the “why” of any learning experience more meaningful and specific. You just need to encourage them and – through prompting and pausing – give them the cognitive space to do so.

7. Pave the Path Forward

I’ve now covered most of what happens during the time that attendees are actually present for your virtual presentation, but what about what comes after?

While rates of forgetting can vary widely from person to person, most of us will forget most of what we hear and see in a presentation within a matter of weeks, if not days or – sadly – hours. So, if you really want your attendees to retain and use what you present to them, your presentation is just one step in a longer journey to fully absorbing and mastering the material you cover.

To ensure that journey is ultimately successful, it’s important to help learners understand the need to revisit and continue to engage over time with the key concepts and ideas covered in your presentation. And it’s also important to provide them with or help them find opportunities for doing this.

So, to wrap up, let’s take a look at how you can help your attendees create a future in which the learning you’ve facilitated sticks and gets put into action.

Provide a map

First, taking the “journey” metaphor to heart, provide your learners with a map. Or, even better, co-create a map with them.

By “map,” I mean a concrete resource like a document or a web page where you suggest clear steps or actions learners may take over time, starting immediately, to ensure that they retain and apply what they have learned.

Depending on the nature of your virtual presentation, these could include anything from trying out a particular method or procedure in different situations. Or it might mean asking learners to make daily journal entries for a period of time to note down when they have applied one of your key concepts and the results they got.

That’s your part of the map.

But it’s also useful to ask attendees to add their own elements to the map – whether by creating their own supplemental resource or providing them with an editable version of whatever you provide. While you probably have a great deal of expertise or experience in whatever topic you are presenting, there’s no way you can know where each attendee is trying to go. The destination – the why, the goal – will vary some from attendee to attendee.

By asking learners to co-create the map – essentially, to identify what they will do differently in the future as a result of what was covered in your presentation – you offer them the ability to personalize the learning experience, to make it as relevant as possible in their specific contexts.

Provide resources

Along with the map, provide resources to support the learner along her journey, as she pursues the actions on the map. These might include things like reference and tip sheets, checklists, self-checks that learners should complete at established intervals, or links to additional materials – articles, books, videos – that help reinforce or expand upon the most essential elements of your virtual presentation.

Again, these can be put into a document or posted to web page.

Encourage accountability

Finally, for the map and resources to have an impact, they have to be used.

So, encourage learners to make clear, measurable commitments to themselves – for example, by setting dates by which they will accomplish items on the map – and to find accountability partners—in their workplace or within professional networks or communities they’re part of to help hold them to applying what they learn.

As part of supporting accountability, you may even want document concrete ways in which a colleague and/or manager can best support accountability—one of the resources you provide may help support this. You might even create a brief guide for accountability partners—i.e., what do you want them to do, when, why?

It’s a Process

One of my mantra’s is that learning is a process, not an event. Just like a single virtual presentation will have only so much impact on your attendees, reading this article will only have so much impact on your presenting. Everything discussed here takes a lot of practice over time to do really well.

But, of course, every journey begins with a single step.

Just becoming conscious and intentional (or, if this is familiar ground, more conscious and more intentional) about what goes into more effective, engaging virtual event presentations is an essential step. Beyond that, continuing to review, practice, and improve at everything covered here over time will ensure that your virtual presentations stand out and deliver real impact.

One last note: while I’ve focused on improving virtual event presentations here, everything I have covered applies to creating content for online courses and, indeed, for most methods of sharing your expertise and helping others learn.

So, I encourage you to bookmark this page, share it with friends and colleagues who might benefit from the information offered here, and return to it periodically to reinforce your own learning.

Additional Reading

Here are some additional resources you may find helpful. (I plan to add to these over time – just one more reason it is useful to bookmark and share this page as a reference).

John Medina’s Brain Rules is one of the main sources for the rule of thumb for chunking content into segments of no more than 10 minutes, As Medina writes:

Audiences check out after 10 minutes, but you can keep grabbing them back by telling narratives or creating events rich in emotion.

You can download all 12 brain rules at the link above.

Chunking Informational for Instructional Design

eLearning Coach Connie Malamed provides some good, concise tips on how to chunk content to ensure you support learning.

How to use Mayer’s 12 Principles of Multimedia

To keep things simple and actionable, I touch on just a few key principles of multimedia above. If you want to go deeper, this article gives a good overview of twelve principles based on the research of educational psychologist Richard Mayer.

Spacing Learning Events Over Time: What the Research Says

This classic research round-up from Dr. Will Thalheimer makes clear how powerful “spacing” is.

See also:

- 7 Keys to Make Money from Webinars

- How to Deliver Great Webinars with Wayne Turmel

- How to Host a Virtual Conference – 10 Tips for Success

- Best Screen Recording Software

Table of Contents